- Home

- Eileen Alexander

Love in the Blitz Page 18

Love in the Blitz Read online

Page 18

Wednesday 25 December Darling, at about eleven I got tired of staying in bed. (Not that I was wasting time, dear, I was turning out thank you letters five to the minute.) I had lovely presents – three vinaigrettes – a gold one & a silver-gilt one from my mother – and a little plain humped one, like a tiny pepper pot from Mrs Ionides – and my mother gave me a hand-bag suspended from a belt as well – quite absurd, darling – but a Great Solace. Mrs Seidler gave me pigskin gloves & Joan Aubertin The Shropshire Lad with Streamlined woodcuts – Mrs Low (who always does the Right Thing) gave me The Bedside Book which I’ve often had before – but I always lose it, so it doesn’t matter. I had enough lavender water to last me for a year of Sundays – & a wonderful assortment of nice smells for my bath – Next time you see me, darling, I shall be perfumed like a milliner – as the Shakespearean phrase is.

Monday 30 December Darling, today has been a bewildering and unreal day – Eliot called London an unreal city under the brown fog of a winter dawn, how much more unreal then, in a stinging curtain of black smoke.

At Chalk Farm Station this morning, they told me that I couldn’t get out of the train at Moorgate – I should have to go to the Bank. I came out of the underground into a blinding mist – I could see people dimly, colliding on the pavements and in the roadway and threading their way among the thick white hoses of numberless grey fire-engines which were blocking all normal traffic completely. My shoes squelched soggily in the wet street, and tiny jets of water from the joints in the hoses sprayed my legs. All the women in the street were splashed with mud-freckles all up their stockings – hundreds of fire-men in tin hats, and anachronistic Asbestos Helmets (they looked like cruel parodies of Roman Warriors, darling) were pushing their way through the crowds – flakes of charred paper were floating down from buildings everywhere and brushing against our smudged faces – and on the dry patches on the road they were crumbled by passers-by into tiny fragments – like blackened lice. I walked dazedly to the top of Moorgate – but I couldn’t get down it – fireman’s ladders crisscrossed in the dimness like monstrous darning needles – and I could see great yellow patches of flame through the empty window frames in the street. On some of the nearer ladders, the tiny firemen looked like flies on lumps of sugar, with their spindly legs outlined against the smoke-clouds. Even in the midst of my horror, darling, I was immediately excited by the perspectives of the firemen’s ladders, disappearing into the fog.

I walked vaguely through the back streets trying to find a way into Finsbury Square – & then Miss Hojgaard tapped me on the shoulder & we went on together – like rolling snowballs, darling, we gathered a mass of bewildered Welfarers as we went along – and, at last, we met Miss Burrows – coughing and streaming & pointing inarticulately to the roofless, blazing shell of what had been 1, 2 & 3 Finsbury Square.

Then we all went to Finsbury Barracks which were always to have been our Emergency Headquarters. The Sentry challenged us – but we Forgot All & simply said ‘Welfare’ – He didn’t shoot us, darling, he just saluted & let us through – & we all stood about Forlornly in a huge & barren room, until the General arrived & told us all to report again on Wednesday morning. Then Miss Burrows & I went to The Great Eastern, lathered ourselves thickly with Antiseptic Soap – and the dirt rolled off in flakes that were the reverse of Hoary.

I brought Miss Burrows home to tea – but I was too saddened to eat any. Oh! my darling, I’ve seen the second great fire – and there was nothing gigantic or elemental about it – it was just destructive and dirty. Of course all my Regimental lists and the office files – are burnt – I fancy there won’t be any more work for me in Welfare, but I shall doubtless Learn All on Wednesday morning.

Darling – shall I tell you something Fantastic? I didn’t sleep all Saturday night – because I was terrified that I should walk up to your room in my sleep to see you – and that no one would ever believe either that I was asleep or that I’d just been to see you, because it was fantastic not to be with you when you & I were in the same house. I wouldn’t blame anyone for not believing me – but it would have been true.

Thank you for coming to stay with us, my dear love. I hope you’ll come again – often – but I’ll never let you walk through an air-raid again – it was the worst half-hour I’ve ever had. D’you know, darling, that when I told you in the cinema that I was frightened of the whistle of bombs, it was the first time I’d told anyone – because, in this house, my mother & I have to preserve an elaborate indifference – because everyone else is in such a noisy cluck (Except Lionel, who is Vociferously Unconcerned.)

I’m too tired to write any more, dear. I’ll let you know further developments soon.

1 Archimedes.

2 London County Council.

3 Inns of Court. Gershon was a member of Gray’s Inn.

4 A character in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield.

5 On the Isle of Man. On the declaration of war there had been about 70,000 Enemy Aliens in the country, and these were divided into three categories of threat by government tribunals, with ‘Category A’ aliens liable to internment. In May 1940, with the fear of invasion in the air and in a climate of mounting hysteria, the first internment camps were opened on the Isle of Man and it was there that Alec Alexander was involved with the work of tribunals and the release of those who posed no threat.

6 F. R. Leavis (1895–1978) was a British literary critic.

7 F. L. Lucas (1894–1967) was a British classical scholar, poet, novelist and critic.

8 Salvation Army.

9 Hamlet, Act IV, scene vii.

10 Food rationing was brought in at different stages of the war, beginning in January 1940 with bacon, butter and sugar, with eggs (one egg per week per adult and dried eggs, one packet per month) first rationed in June 1941.

January–March 1941

Nineteen forty-one will be remembered as the year a European conflict became truly global and Britain and her empire found themselves allies. Britain had never had to ‘stand alone’ in quite the way that propaganda and national myth suggests, and yet it was not until the war became a world war, with Germany’s invasion of Russia in June and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, that Britain could see a chink of light at the end of a very long tunnel.

If it would be hard after America’s entry and German reversals in Russia to see how the war could be lost, it was just as difficult in these early months of 1941 to imagine how it might be won. On either side of the new year there were some facile and spectacular successes over the Italians, but with the Luftwaffe devastating Britain’s western ports, and German U-boats and surface vessels wreaking havoc among Britain’s vital Atlantic supply lines – almost 700,000 tons of shipping were lost in April alone – there would be no ringing of victory bells for another twenty-odd months.

Nor was the worst of the Blitz over – the heaviest raid on London would be the last, on a ‘bomber’s moon’ night of 10/11 May 1941, when more than fourteen hundred people were killed and the Chamber of the House of Commons burned to the ground – and few major cities would escape. The attack that destroyed the Welfare Offices in Finsbury Square had also devastated much of the City, and at the start of the new year Eileen moved with Nathan’s ‘Welfare’ to temporary offices in Buckingham Gate, and it is from her desk there that many of the letters from these next months were written, letters full, after the ‘black hole’ of the late autumn into which she had sunk, of all the old signature mix of ‘willy-nilly,’ and ‘cluck’ and – hesitant at first, but increasingly insistent –‘Intentions’.

One of the main reasons for the shift of mood was that Gershon had also moved from his old camp near Blackpool to Calne, Wiltshire, though after seven months of RAF camps and courses a commission seemed as remote as ever. There seemed a glimmer of hope in February when his old Cambridge professor put him forward for a job psychologically evaluating aircrews, but the minimum age for a commission into the intellige

nce branch was twenty-five, and at twenty-four, a frustrated and often moody Gershon could do nothing but mark time and contemplate the grotesque thought of having to salute Charles Emanuel.

As a trained wireless operator working through the Blitz, however, Gershon would have been a small but vital cog in the intelligence war against the Luftwaffe. The popular story of British intelligence during the Second World War inevitably focuses on the codebreakers of Bletchley Park, and yet just as crucial were the men and women of the less-well-known ‘Y Service’, service personnel and civilian ‘hams’, based in listening stations across the country and the world, who were the ‘ears’ of ‘Station X’, as Bletchley was called, listening through their earphones around the clock to the cacophony of encrypted enemy signals and voices that filled the air and feeding them on to the Bletchley codebreakers.

How much of all this Eileen knew is impossible to say – her letters naturally give nothing away – but in February a letter arrived from the Air Ministry inviting her for an interview. If she could not be with Gershon she might at least be able to feel that they were working for the same ‘firm’.

5

Intentions

Wednesday 1 January 1941 Goodmorrow, love – and a very happy New Year to you. I walked past the still smouldering ruins of Welfare Branch, Eastern Command & London District – and Reported at Finsbury Barracks. I showed my pass to an extremely ’igh-class sentry with an Oxford Accent, who sent me upstairs to a Barren Room, where I found Mr Parr Sitting in State behind a large deal table – and loving it. I was sent, with Miss Green (a flat-faced woman, darling, with a lecherous eye & Piccadilly Circus clothes – but nothing ever came of them) and Miss Dupois (In charge of the filing room – (as was) She has an extremely Genteel voice – but when you ask her to do anything, she replies surprisingly and monotonously ‘Righty-ho. Righty-ho’. An expression hitherto unknown to me) to 25 Buckingham Gate. The General looked at me, more in sorrow than in anger, and said that, as there was nothing I could do for the present, I’d better go home & Call Again Tomorrow. (I felt just as though I’d been trying to sell him a Hoover, darling.)

I knew my parents were going to have sherry with Leslie before lunch (he’s in bed with a duodenal ulcer, and conspicuously Solaceless) I rang them up from a nearby call-box and suggested that I should meet them at his house, which is about three minutes walk from Buckingham Gate.

Have I ever described Leslie’s house to you darling? It’s built of mellowed, smoky 18th century brick and is sandwiched between two much taller houses. It is small, but gracious. He collects powder blue and almond green Wedgwood china – and he has three lovely urns in the fanlight over the front door and delicate little plaques with dancing figures set into the woodwork of his drawing room. The woodwork is light & unpolished and all the upholstery is dull gold brocade.

His bedroom (which I’d never seen before) is designed for Wantonness, darling – a huge, curving, French bed, with pastoral scenes and rich medallions of fruit and primrose sheets and pillows, with his monogram everywhere. There are a few delicate French chairs and a smallish arm-chair – but they’re obviously just to fill up space and don’t matter in the least.

He lay back on his pillows in Wedgwood-blue flannel pyjamas (a pretty touch, darling) with greyish curls all over his chest and arms, and Thundered forth his war-aims and his Indictment of The Party System. He then asked me All on the subject of Duodenal Ulcers – and listened with passionate interest to everything I said. He rubbed his wispy locks into greater disorder still, and said that to win wars one must Attempt the Impossible. We left him in the process of Winning this War, from his bed – Picked our way gingerly down the narrow stairs, and nodded an absent-minded goodbye to the Marble Statesmen in the Hall – & came home. Leslie is a Great Solace, darling. He reminds me a little of Romeo, before he met Juliet – Wilful, Whimsy – and petulant – but he has a touch of Mercutio about him too. It’s a pity he never married, darling.1

Thursday 2 January Darling, Miss Burrows told us that when Lord N[athan] Heard All, he Paced Up and Down, muttering, ‘30 years’ then Struck an Attitude and Bellowed ‘We Must Have a Broadcast’.

She then told us the Sad Story of How She Lost her Underwear – You see, darling, the Thing is This … Last week Miss Burrows bought a pair of lady’s dustsheets – She left them at the Office – but in order to spare Mr Herbert any Embarrassment lest he should have to search her desk for an important document, she put them in a Foolscap envelope & marked them ‘Personal’ – and now they are Gone Forever – but a new word has been added to the language – because it’s obvious that Henceforth, all lady’s dustsheets must be known to Us and all our Intimates as ‘Personals’. Take off your hat in the Presence of the Dead, darling, as Mr Corbel (he who caused Mrs Bacon to leave Welfare & go back to Commerce – because he imagined mistakenly (having Seen All that existed between Her and the Man who is not Mr Bacon) that she was a Multi-mollocker – and on that assumption kissed her hand – (It was the Velvet Tights and Golden Rinse that Got Him, I think)) said as he rushed with Another into the blazing wreckage on Monday morning, to Rescue his Compensation Cases and carry them out on a Tea Tray. (The results of his Heroic Action (all this is perfectly true, darling) were delivered at our new HQ this morning marked ‘Salvaged from the ruins’.)

Sunday 5 January Darling, I have just Risen, much more like a boiled shrimp than Venus, from the foam of a scalding bath and, although my body is the colour of raspberry soufflé, I’m not warm yet.

Talking of Leslie (I did refer to him) I forgot to mention his comment on Churchill’s Rallying Call to the Italians.2 He said that that was not the way to Foster the Seeds of Dissatisfaction in Italian breasts. After all, he said, with an enquiring glance from one of my parents to the other, when a husband & wife were quarrelling, the one certain way of driving them back into one another’s arms was for a third person to start abusing one of them. At this the other would Rally to the Abused One’s side and Turn Fiercely upon the Abuser – That, he affirmed, was Human Nature. It’s certainly true in respect of my parents, darling, and of most other married people I know as well as that; it remains to be seen how true it is of Mussolini and Italy, his Unmarried Wife.

The Nazis have started day raids on London again, darling – (We haven’t had any for several weeks). It’s very tiresome of them.

Monday 13 January Darling – I’m getting so tired of Welfare. The type-writers clatter all round me like teeth on a frosty night – (particularly my teeth) and everybody bickering with everybody else – and Miss Leonard, (whom I calls CIGS3 Because she has a taste for pushing us about on a Chart as though we were Counters representing Army Units) putting her finger in every pie and then sucking all the plums off the end – (She never interferes with me, darling, so I don’t mind her – but poor Miss Carlyon – and Miss Burrows and Miss Crook).

Have you heard anything from the Air Ministry? Darling, not the least frightening aspect of your going away is the thought of Pa’s attitude which will be a What-are-you-clucking-about-he’s-not-your-Intended-or-anything-what-you-need-is-to-meet-more-Young-Men-one.

Wednesday 15 January I walked across the Green Park through the snow today – the tree-trunks were white all down one side and the branches lightly powdered with snow – Such lovely shading, darling – (Oh! I do love shape and shading & perspective – but I love colour too) and the Belisha Beacons4 all had little white, furry caps – and the waste-paper bins had crisp little rims of snow round them – I don’t know how I ever did without snow – before I’d seen it – I don’t mean tracts of snow, such as I’d seen in Italy & Switzerland before I ever came to England for a winter – but intimate, domestic snow – which is much more of a Solace. I think that’s why I hated Egypt so much – no snow – no Primroses – and no Gershon (Heaven’s last, best Gift) – a barren country, darling.

Thursday 16 January A Beautiful thing happened today. A Stalwart Police Sergeant pushed his hea

d Purposefully through the hatch and said: ‘I want to see Colonel Lord Nathan of Churt.’ ‘Well, he isn’t here,’ I answered – ‘Very well, I’ll wait until he comes,’ he said – obviously prepared to wait for the Duration if necessary. ‘Well – er,’ I went on timidly – (I could see he was the kind of man who would Wear Down a Stone until he got to the Blood) ‘He never comes here.’ ‘No?’ he said, Sceptically. ‘Well this letter,’ (he waved a type-written sheet of Paper at me) ‘has this address at the top.’ ‘Oh! yes,’ I explained. ‘These are the Headquarters of Welfare – Eastern Command & London District – and he is the Director of Welfare, you know. Perhaps you’d better see General Buchanan – he’ll tell you how to get in touch with Lord Nathan.’ He gave me a Look at which a Strong Man would have Wilted – let alone your poor little Cluck. ‘Lord Nathan,’ he said slowly & ponderously, ‘is going to be Seen by the Police – He needn’t think he is not Going to Be Seen by the Police – It’s a Case of Firearms.’ This was becoming Exciting, and I said: ‘Well, the only way you can get to Lord Nathan is by seeing General Buchanan first.’ ‘Very Well,’ he said – Getting It at last, ‘I Shall See General Buchanan.’

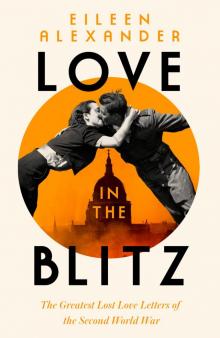

Love in the Blitz

Love in the Blitz