- Home

- Eileen Alexander

Love in the Blitz Page 4

Love in the Blitz Read online

Page 4

Dad is certain that there will be peace with honour. Well! if he’s right, we shall meet again at Ismay’s wedding in just over a fortnight, sha’n’t we? If he’s wrong – ‘Quoth the raven “Nevermore” –’7 or quite possibly, at any rate – but this is vapouring. Take no notice of it.

Monday 28 August I had an agitated letter from Joyce by the same post as your two. If there is a rent in the clouds – she is coming up here at once – otherwise she will be evacuating school-children for her Country.

I liked the fatherly touch about ‘one oughtn’t really to worry about individual skins’. Of course one oughtn’t, mon cher, but one does – and the more shocked one is by the unethicalness of worrying, the more one worries, because in addition to worrying, one worries about one’s own shortcomings which make one worry – if you see what I mean – and I shouldn’t blame you if you didn’t. Anyway, (and I say this defiantly, though firmly) I’m glad you’re not a Territorial – though I don’t suppose that will prevent the War Office (damn it lustily) from sending you off to prod Germans in the rear from the Maginot Line, while they are busy trying to squeeze into the corridor, if & when war breaks out.

Of course, I was saddened to hear that you had had my blood cleaned off your suit – but I do see the position. It would have been a fine gesture to arrive at Ismay’s wedding all spattered with it – but it might have caused Comment or even Gossip – and then – Reputation, Reputation, we’d have lost our Reputation – which would have been a pity – but it was uncommonly civil of you to say you wouldn’t let anyone else bleed on it. If anyone tries, just push her onto the ground, and let her bleed on that!

I haven’t had an answer to my letter to Miss Sloane (Leslie’s Secretary) yet – but I pressed obligingly but firmly for a job either with the War Office or the Censorship, on the outbreak of War – (if such there be). I could not possibly spend the illimitable duration of a modern war in the family bosom – we would worry one another around in circles all the time, until one, or all of us, dropped down dead, from nervous exhaustion. If I have a paid job in the government, I shall have to go where I’m told, and no-one will be able to do anything about it, which sounds incredibly selfish – but actually will be better for all of us.

(By the way, I hope our Aubrey is safely back from Geneva.8 Joyce has had two post-cards from him since he left England. I have had one letter – which of us is better off? It is hard to day. I wrote him a very silly letter, to which I have not, as yet, had any answer – but I hate to think of him perishing in a mined Swiss Mountain Pass – or being drowned by conquering Nazis in Le Lac Léman. Oh! dear, what a woeful thought.)

Wednesday 29 August If there is no war, we leave here next Tuesday evening and hope to arrive in London on Wednesday morning – (bless we the Lord. Let’s praise & magnify him for ever, if we are able to proceed according to plan). Excavations on my tooth are scheduled to begin on Thursday 7th – but I don’t think my chin will be quite itself again in time for Ismay’s wedding. It is getting paler – but slowly. Eventually I think it will disappear altogether (I mean the redness – not (I hope) the chin!) but not for some time, yet.

Friday 31 August Your letter has just arrived, Gershon. Your reprimand was more than justified and, in the circumstances most kindly expressed. From now onward, the expression ‘I shall never be the same again’ will be wiped from my epistolary slate for ever, though it is only fair to warn you that, after taking this drastic step, I shall never be quite the same again! And there is a condition attached. ‘Sweet-darling’ must be immediately erased from your vocabulary. It does not suit you – or me – and it is not funny.

I thought, like you, that we had the Führer in a corner – but now I don’t know. I don’t understand anything, & I want to say – I’m glad you only feel a healthy glow. My inside is now minced as well as mashed. Thank you for your solicitous advice about what I should do in the event of war – (in this, you and my parents are at one – we have established an armed neutrality on the subject – there’s no point in arguing with them until I hear from Miss Sloane). I could not possibly stay here more than a week or two if there was a war. I am perfectly healthy now – but in a very dangerous state of restlessness because I have nothing to do. When I say dangerous, I mean that I haven’t forgotten that nine weeks ago I was sure I was going mad, (this state of mind was only indirectly due to the accident – ever since I was eleven or twelve, at all times when my mind was not fully occupied with work which was tough & impersonal, I have watched myself fearfully for signs of a lack of mental equilibrium – I don’t know why – I just did) and unless I have some very definite and absorbing work to do, soon – I shall get worse.

I had a letter from Jean this morning. She has been mobilized – at which she is not amused – nor am I, for that matter. As a member of the auxiliary air force, she will spend the entire duration of any war training recruits at humming aerodromes all over the country. She is the only one of my 52 first cousins (except Victor, whose face I slapped, but with whom I am very friendly for all that – which, on the whole is magnanimous of him) of whom I am really fond. Victor is in Corsica – no-one quite knows why – but he’s like that. I fancy, if there’s a war he’ll have to stay there. As he has literary aspirations, he will probably write a book – after all Boswell did.

Now that Ismay’s wedding is post-poned, (sorry – wrong word – I mean now that it is a ‘fait accompli’) I presume that we shall not leave Clunemore on the 5th, unless something absolutely definite happens one way or another before then – but I don’t know. If the status quo is maintained, during the next few days, perhaps you would very graciously go on writing to this address – also, if war breaks out. If anything unexpected happens in the way of a Peace conference or the like – then I expect my address as from Tuesday, 5th will be ‘The Mayfair Hotel, Berkeley Square, London W1’ (Note the forward manner in which I now just take it for granted that you are going to write to me! Oh! Indubitably, I am not what I was! Hubris again, Eileen – oh! Nemesis is close at hand – beware).

Oh! by the way, to revert to this photograph question. When we last met, you asked me for a photograph of my countenance, if and when it returned to its old ‘chubby’ symmetry. (Ill as I was, I was touched at your choosing the word ‘chubby’ in preference to ‘fat’. These are actions that a king might show.) On the strength of this request, I bullied you into having your photograph taken for me. Now I feel in duty bound to ‘fulfil my obligations’ if you wish to hold me to them. (It most certainly is not too late to withdraw – negotiations have hardly started. I can’t even have proofs taken, until my broken tooth is restored – but let me know, and I shall, in all my best, obey you, sir.)

1 A reference to ‘The House of Fame’, a poem by Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343–1400).

2 Beth Din or ‘house of judgement’ is a rabbinical court of Judaism.

3 In 1935 Mussolini had brutally invaded Abyssinia in defiance of the League of Nations, driven the Emperor Haile Selassie into exile and proclaimed a new Roman Empire. Fearful of war with Italy at a time of the growing German threat, Britain, like France, had shied away from effective sanctions and allowed Italian warships unhindered access to the Suez Canal.

4 From ‘Intimations of Immortality’ by William Wordsworth (1770–1850).

5 Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War. An old friend of the Alexanders, he had holidayed with them at Drumnadrochit.

6 Neville Henderson, British ambassador to Germany 1937–39 and a supporter of appeasement. The telegrams reported Hitler’s determination to invade Poland and blame England for any consequences.

7 From The Raven, a narrative poem by Edgar Allan Poe (1809–49).

8 On the outbreak of war, Aubrey Eban was at the 21st Zionist Congress in Geneva.

September 1939–April 1940

With the German and Soviet invasion of Poland, war had become all but inevitable. On the same day that German planes bombed Warsaw, Bri

tain’s army was mobilised, and as the evacuation of mothers and children from major cities began, and London sank into the darkness of the first blackout, the country waited every hour for the declaration of war that still did not come.

At 9 a.m. on Sunday 3 September, after another two days prevaricating, Chamberlain finally bowed to Cabinet and parliamentary pressure, and an ultimatum was delivered to the German government. At 11 a.m. it expired unanswered, and the country finally, and unheroically, stumbled into war. Six hours later, an even tardier France followed suit. The long ‘half-time’ of peace was over.

This would be the last summer the whole Alexander family would spend together at Drumnadrochit. That Sunday morning they sat around the wireless and listened to the prime minister’s broadcast to the nation, and as their holiday neighbour, Mrs Ironmonger – an aspiring Lady Novelist who had tormented Eileen with her unpublished manuscript – hurried back to Liverpool and ambulance duties, and her son to his Territorial unit, a frustrated Eileen was left in her Highlands limbo, with her parents, brothers, family nurse and the Alexanders’ customary gaggle of hangers-on, wondering what she was going to do.

In these first weeks of the ‘Phoney War’, when no German bombers came, and the RAF dropped leaflets on Germany, and city evacuees drifted back to their homes, a curious sense of anti-climax settled over Britain. On 4 September the first advance units of the British Expeditionary Force had sailed for France, but the only real fighting was taking place a thousand miles to the east, where a doomed Poland fought on alone.

When more than a month later Eileen finally returned with her mother to London, before going on to Cambridge to begin her research on Arthurian Romance, it was certainly the normality of home-front life rather than its strangeness, that would have struck her. The Emergency Powers Act (Defence) had given the government dictatorial powers over the whole gamut of national life, and yet while barrage balloons floated above London, air-raid wardens patrolled the blacked-out streets and everyone now carried ration books, identity cards and gas masks, the cinemas were again open, rationing – except for petrol – had not yet begun, the gas and bomb attacks had not materialised, and ‘everything that was supposed to collapse’, as Eileen’s great friend Aubrey Eban recalled, ‘went on exactly as before’.

It was the same when Eileen moved into her rooms at ‘Girton Corner’ in the middle of October, with Cambridge very much the Cambridge she knew and many of her old friends still up. On the outbreak of war, Parliament had brought in conscription for all men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one, but Gershon’s age group had not yet been called up and he was back at King’s, studying law, starring in union debates alongside Aubrey, and exchanging notes and letters with Eileen, just three miles down the road, as if the war did not exist.

War, however, was closing in. On the day that Eileen and her mother had left Drumnadrochit for the Mayfair Hotel in Berkeley Square, Poland finally succumbed, and German armies began their move from east to west. In December the Battle of the River Plate gave the British public a rare victory but the New Year brought little else to cheer. Abortive plans to help Finland and simultaneously deny Germany Sweden’s iron ore would lead to the chaos and humiliation of the Norway campaign. Merchant losses at sea prefigured the long and desperate fight against the U-boat that lay ahead and by January the first food rationing – sugar, butter, bacon – was introduced. Before the New Year was a week old, too, the Alexanders’ much-loved old friend, Leslie Hore-Belisha, the Secretary of State for War, bitterly at odds with his own generals, had been sacked.

As Eileen prepared to return to Cambridge after the Christmas vacation, across the Channel the BEF dug in along the Belgian border next to their French allies, and waited for an attack they were ill-equipped to resist.

2

‘No time to sit on brood’

Friday 1 September 1939 On hearing Hitler’s ‘peace’ proposals over the wireless last night, I begin to feel a warm glow at the idea of punishing the insolent brute, as well! The beautiful impertinence of the suggestion that – (given twelve months for the dissemination of Nazi propaganda & terrorism in the Corridor) he would like another of those now-notorious cooked plebiscites – is really almost inspired! I don’t think even our simple-minded Neville would fall for that one again, somehow. Do you?

I have now heard from Miss Sloane. There is nothing but clerical work at the War Office for the present – but she advises the Censorship. I should apply immediately, she says & I shall probably have to take an exam, soon. Thank God for that. Can’t you see, Gershon, how I come to life again, at the very prospect of something to do?

I had a pathetic card from Ismay this morning. She is staying in Sussex with Charles. He can’t be far away from London, as he expects to be called up any day.

I have written to the Censorship office, telling them how clever & useful I am, and how silly they’d be not to have me. I intended to write the letter myself, but I turned all bashful at the last minute & couldn’t take the responsibility for such a lot of lies, on my own shoulder – so Dad dictated a gem of a document. If you only knew what a mine of precious ore you’d held, bleeding down the front of your suit, ten weeks ago – you’d never have sent the suit to the cleaners.

I presume that owing to the outbreak of hostilities between Germany & Poland this morning – the declaration that we are at war, will be put before the House this evening.

You are likely to have a great deal to do, and worry about during the next few weeks. Please darling, if you are bothered or busy, don’t attempt to write me long letters. I’d be glad of post-cards – to know how you are, and letters if and when you have time – but I’m no longer an invalid who has to be humoured – and all men who are likely to be conscripted will have to think primarily of themselves now, and not of spoilt & idle women to whom they have already been over-indulgent.

Saturday 2 September We shall not be leaving here on the fifth, and I shall stay here until I have definite work to do – which I hope to God will be soon.

Sunday 3 September We have just been listening to Chamberlain’s announcement that we are at war. There is nothing more to be said except God bless you and keep you, and everyone else who is going to help in blotting out slavery & brutality, from too much sorrow and pain. I’m afraid this sounds banal – but I mean it, Gershon.

Let me have news when you can – because I shall be worrying and wondering, at all times, about the whereabouts and safety of all my friends in vulnerable areas – but once again let me reiterate that a post-card will be enough if you haven’t the time or the inclination for letter-writing.

You must be worrying a great deal about your parents. Has your younger brother been sent away to a place of safety?

Under the new Conscription Act1 – I suppose you will soon have to start training for a commission.

This declaration of war has had an astonishingly Cathartic effect upon me. ‘I have not youth nor age – but, as it were, an after dinner sleep, dreaming of both.’ The rain is coming down in a thin drizzle and there are wisps of fog crossing the tops of the hills. It is very dark.

We are as safe here as we could hope to be anywhere. Don’t worry about me, please. I am getting better astonishingly quickly, and soon, I hope – I shall be perfectly fit to do useful work wherever I can be of help.

I hope you are less thin & tired than when I saw you last. Forgive my clucking (nature will out) but do take a tonic if you’re not – an army marches on its stomach, after all – & people with concave tummies have to crawl along on their ribs – which is uncomfortable.

Good luck, Gershon darling, and (as Miss Sloane said) may we soon meet again in Peace.

Don’t be alarmed at the solemn, not to say sententious, tone of the last part of this letter. I can & shall smile still, but I did want to say just once, quite seriously, what I was thinking. It won’t happen again.

Monday 4 September I hope you wer

en’t disturbed by the Air Raid Sirens last night. I hope you never will be.

I hear the Government urgently wants Graduate University students (men) urgently for all kinds of work. Mum says they broadcast a request for volunteers, while I was having my walk.

I have a premonition that you were born to be the Brains behind this war – be guided by it, Gershon.

Wednesday 6 September I had another letter from Joyce this morning. She is definitely going back to Girton next term. I think she’s wise. I would do the same, were it not that I feel compelled to try & be as useful as possible – and I shan’t do that by digging myself deeper & deeper into the middle-ages. I simply cannot go on living on my parents any longer – though they would, not only willingly, but gladly, go on supporting me in luxury forever. I have, however, written to the Mistress of Girton,2 asking her if there’s any work I can usefully do in Cambridge – and to Miss Bradbrook. I’d be happier there, than in a strange sea-port, prying into other people’s private letters. But if neither the Censorship nor Girton can make use of me, then I think I’ll write to Dr Weizmann & see if he can include me in his scheme for organizing Jewish brain power!! The old boy is about as fond of me as the Chief Rabbi is (I have found it necessary at times to use the same methods of intimidation upon him – when he comes over the heavy leader and martinet) but surely he won’t allow personal prejudice to interfere with the Public Weal – what d’you think?

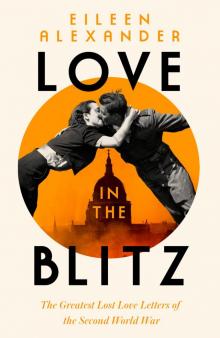

Love in the Blitz

Love in the Blitz